a slow march towards vim

Introduction

So I've decided to button down on vim as part of my new refreshed developer setup, and part of that is me having to (re)learn vim. I'll be documenting my journey here to keep myself honest and to have a reference of sorts so I can quickly lookup things.

This is not a very technical (or in places, may not be that accurate) document or comprehensive guide to vim. There is a LOT to learn, which is why I created this to help me focus on the important parts to get me to start using vim quickly for the majority of the tasks I need.

See part 2 for more on windows and buffers.

There's a list of references at the end of this post which I highly recommend if you want to dig deeper into this.

Why vim and not xyz?

I get it - everyone has their favorite editor, and I too remember the glory days of emacs vs. vim and the ever favorite tabs vs. spaces debate.

However, these days I realize I need to simplify and multiply; meaning limit how many ways I have of doing something (see: the paradox of choice) and then multiply that effort across other areas.

I'm not sure if this experiment will work, but so far I am enjoying getting into a tool that I've always used, but never really understood.

The reasons I'm choosing vim:

- its almost universally available, doesn't need to be installed (well,

viis, more on that later) - its keyboard-first

- it has great regex support

- many other things, including GUI editors and shells support its keybindings

vim vs. vi vs. neovim

vim for (vi improved) was created from stevie, which was a clone of the original vi by Bill Joy. vi is 48 years old and parts of it are codified as a POSIX standard. I think they just made software differently back then.

vim has a lot of improvements that really make it more user friendly (and also, some changes that make it incompatible with vi). Its not important the exact changes (wikipedia has a list if you are so inclined). I wanted to mention it here because these are two different programs.

neovim is a refactoring of vim to enable more plugins, move to lua from vimscript, and provide a greater out of the box experience for new users (read more about the vision of neovim).

Then there are packaged configurations (also called distributions in some places) on top of neovim, such as lunarvim, lazyvim & others. I'm using lunarvim for my setup.

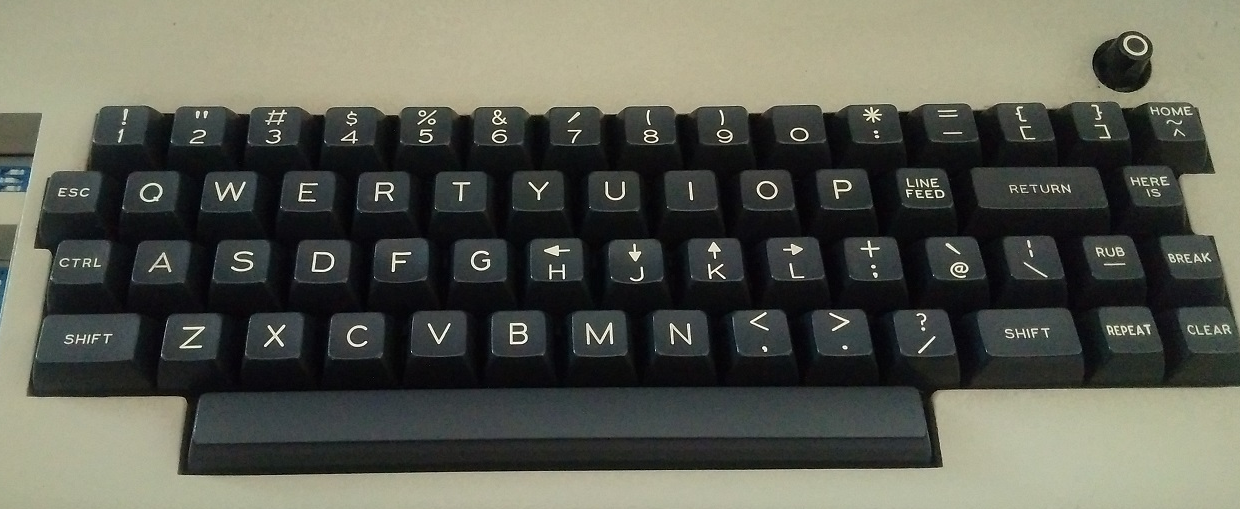

If you are wondering like I did, why h,j,k & l are the equivalents to

the arrows keys and not the actual arrows key symbols its because of this very important piece of

technology: the ADM-3A terminal.

ADM-3A keyboard (image credit: vintagecomputer.ca) via Dave Cheney

I discovered just what a critical piece of tech this is from this piece by Dave Cheney (creator of Go).

It is also why the ~ key is the shortcut to the home folder.

modes, buffers, registers & commands

Here are some key things I found helped with my mental model and understanding vim.

modes

So the first thing one has to understand about vim is that it has these main modes:

- insert, for, well, inserting things (making changes)

- normal, for navigation and other functions

- visual, for selecting things

- command, for entering commands to the editor

On startup, vim will be in normal mode. How do you know this? Well, quite simply if you start typing anything, nothing will show up on the screen. Your keypresses are being interpreted as commands. It doesn't matter if you open vim without a file, or with a file. It always starts in normal mode.

Normal mode is for navigating the contents on the screen, and for some modifications. Unless you are inserting things, you should almost always be in normal mode.

Press i to get into insert mode. In this mode, what you type is displayed as-is. To get

back to normal mode, press the ESC (escape) key.

I'll skip visual mode for later.

buffers

The next important thing about vim is buffers. A buffer is a spot in memory, that is used

for multiple purposes. For example, when you open vim with a file, the file is loaded into

a buffer, and then a window is shown over that buffer, which is what you see on the screen.

If you open vim with multiple files (vim one.txt two.txt) vim will create two buffers, one

for each file. Windows are not linked to buffers. A window is just a view onto a specific buffer.

You can open multiple windows and switch whatever buffer each window is currently displaying.

Think of this like split views in other editors.

Windows and buffers are things that work in the background, but knowledge of them really helps when you are trying to figure out more complex tasks, such as viewing multiple files simultaneously, copy & paste and few other things.

registers

Registers are temporary spaces to hold text and other data. The most common use for these

are for copy/paste. You can create your own, but most of what you do is done with the

default register (denoted as "). This is the register that is used to store things you have

yanked (copied) or deleted (cut).

commands

Finally, we get to commands. Commands are how you get anything done. There are three ways to execute commands, or three kinds of commands:

Ex1 commands. These are commands that follow the pattern:such as the famous:qto quit.- Editing commands. These commands you use in normal and insert modes. Such as

xto delete a character, anddto delete a line. - Mapped commands. These are complex commands that are mapped in your configuration files.

lunarvim& extensions provide these commands, and you can create your own.

No matter how you execute them, commands are the essential secret sauce of vim, and thus the one area where it makes sense to spend some time to understand the vim mental model. The productivity and speed that makes vim such a favorite comes from understand the commands and how to use them effectively.

The last thing to know about commands is to know what mode you are in, because

commands are specific to modes. If you are in insert mode, and you type x, hoping

to delete a character, you'll just get a x on the screen.

understanding commands

So the modes and buffers are there, but daily use you'll be working with commands, and there are a few tricks with commands, and this is where you'll really get the most bang for your buck.

the vim mental model

The first thing is understanding how vim wants to help you, and it starts with repeating. Our work

is repetitive, multiple commands to repeat the same thing, <backspace> four times to delete four

things; hit the <spacebar> four times to indent, <right arrow> five times to go forward five

spaces, and so on.

The second thing in vim is, there is usually more than one way to do the same thing.

Keeping this in mind, lets take a simple example. I want to delete three characters, so how you would do it?

- place the cursor at the first character

- hit the delete key three times

In vim, you could do exactly this (x deletes a character). So you would place the cursor at the first

character, make sure you are in normal mode, and then type xxx and three characters would be deleted.

Or, you can type 3x (which is, repeat 3 times the following command). Now, you want to delete

the next three characters, so you'd just type in 3x again, and repeat to delete in batch of 3s.

In fact, there is a special command, the dot command (.) which always holds the last completed, combined command executed.

So what you would do is 3x, then ... to repeat the previous command.

Here's the thing though, it stores the last completed

command, which means if you do iHello<space>World<Esc> this is a complete command which is:

iinsert modeHello<space>World(the literal characters)<Esc>(the escape key, to exit from insert mode)

So what happens if you type . after this sequence iHello World<ESC>?

Hello WorldHello World

Once you start getting this pattern, the rest of the power of vim unlocks.

command patterns

There's a lot to unpack here when we get to commands and patterns, so sticking with the getting the mental model, here are a few things to keep in mind:

- vim works on a concept of text objects, which are a series of characters of n length.

- a command is a combination of a count, an operator and a motion with the syntax

[count]operator[motion] - only the operator is required

- motion scopes the operation; in other words, it defines the text object on which to execute the command.

In practice, what that means is when you do execute this: 3x, it really is:

- the count is

3 - the operator is

x(delete) - the scope or range (the text object on which to operate) is the default, a single character.

Here's another example d5j, this is actually two commands:

-

the count is omitted

-

the operator is

d -

the motion is omitted

-

the count is

5 -

the operator is

j(down arrow) -

the motion is omitted

This translates to delete 5 lines down. The other way to get the same result would be 5dd (dd deletes the entire line).

There are common patterns for commands, like the 3x trick above. Lets

dig into a bit more of an example, with the following:

wjump forward to the start of the word (Wcounts words with punctuations as one word)bjump backward to the start of the previous word (Bcounts words with punctuations, but backward)uundoddelete$jump to the end of the line (g_jump to the end of the last non blank character in the line)0jump to the start of the line (^jump to the first non-blank character of the line)

Lets take w as an example. This is a command for cursor movement, but you can combine this with other patterns:

3w(move forward 3 words)d3w(delete three words)^d3w(go to the start of the first word in the line, then delete three words)$d3b(go to the end of the line, and delete the last three words)

Another pattern is upper case / lower case characters (you noticed this with b and B), but this

pattern permeates in other commands:

iinsert before the cursor andIinsert at the beginning of the line.aappend after the cursor andAappend at the end of the line.oappend (open) a new line below the current line andOappend (open) a new line above the current line.

Yet another pattern is to repeat the command to change the scope:

dddeletes the entire lineyyyank "copy", the entire line

As you start using vim more, watch out for these patterns.

movements

Like the name suggests, movements are series of commands to move around the buffer. You've seen some already (h, ^ and 0 for example),

but here are some of the most common ones and what they formally mean:

| command | action |

|---|---|

h | move left one character |

l | move right one character |

k | move up one line |

j | move down one line |

w & W | move to the beginning of the next word or WORD |

e & E | move to the end of the current word or WORD |

b & B | move to the beginning of the previous word or WORD |

f{char} | move to the next {char} on the current line |

F{char} | move to the previous {char} on the current line |

t{char} | move to the character before the next occurance of {char} on the current line |

T{char} | move to the character after the next occurance of {char} on the current line |

( | move to the beginning of the previous sentence |

) | move to the beginning of the next sentence |

{ | move to the beginning of the previous paragraph |

{ | move to the beginning of the next paragraph |

0 | move to the beginning of the line |

^ | move to the first non-blank character of the line |

$ | move to the end of the line |

g_ | move to the last non-blank character of the line |

gg | move to the beginning of the file |

G | move to the end of the file |

jump around get up and get down2

- If you want to jump to a particular line in a buffer, try

nG, where n is the line number. You can also:nto jump to that line. - If you want to open a file and place the cursor at a line number,

vim +n filename, where n is the line you want to place the cursor on. - For large files, you can place marks with

m<letter>, such asma. Then, to navigate to that location use`ato jump to that location. To see all your marks, use:marksand:delmarks <letter>to delete a specific mark. Once a mark is set, you can use them in combinations with other commands. For example,y'a, which is yank (copy), from the current position to marka. - There's a default mark,

', which you can use to jump back to where you were before you jumped around. Forgot something at the top of a file?gg, then`'to get back to where you where.

searching

This should be a major section on its own, as there is a lot you can do with search and replace in vim, but as we are talking about navigating around, here are some tips to search for a specific thing and place the cursor there.

/somethingsearch forward for the next occurance of a word or phrase. Press<Enter>to jump to that location.?somethingsearch backwards for the previous occurance of a word or phrase. Press<Enter>to jump to that location.- Once you have searched for something (with

/or?), you can usenfor the next match, andNfor the previous match. *will search forward for the same word that the cursor is on.#will search backward for the same word that the cursor is on.

selecting the right text objects

There is a wonderful language and capability within vim to select a specific kind of text object, which is a series of character sequences.

I personally love how specific (some may say pedantic) these are. You'd use them in combination with a command to scope the command to that specific text object. See if you can spot a pattern.

| command | object |

|---|---|

iw & iW | inner word; the word itself, without any surrounded whitespace |

aw & aW | the word; including the surrounding whitespace |

w & W | go to the beginning of the next word or WORD |

e & E | go to the end of the current word or WORD |

a' & a" | a string surrounded in either single ' or double ", quotes (including the quotes) |

i' & i" | a string surrounded in either single ' or double ", quotes (excluding the quotes) |

is & as | a sentence, either i (without) or a with the surrounding whitespace |

ip & ap | a paragaph, either i (without) or a with the surrounding whitespace |

i[ & a[ | text inside the [ ] pair, either i (without) the [] or a with the [] |

i{ & a{ | text inside the { } pair, either i (without) the {} or a with the {} |

i< & a< | text inside the <> pair, either i (without) the <> or a with the <> |

it & at | text inside a HTML tag (without or with the tag pair) |

i> & a> | a single tag, so <foo hello="world"></foo>, with the cursor inside <foo, then di> will get you <></foo> |

As you can see, there are a lot and you can get even more, with additional plugins.

text objects, boundaries & commands

Putting the concept of text objects and commands together, to tell vim what you mean comes into play in some strange ways, consider this example:

Would you like to eat some cake?

^

The ^ represents the cursor position

We would like to replace some with more because who doesn't like more cake? So we need to delete the wword, lets try this:

Would you like to eat cake?

^

Next, we want to insert the word more. imore:

Would you like to eat morecake?

^

Not quite what we want. We want to tell vim that when we say w, we mean the word, without the trailing space, to do that, lets start again but this

time we'll use diw, which is delete inner word, with the same initial state:

Would you like to eat some cake?

^

Now, with diw, we get:

Would you like to eat cake?

^

Now when we do imore, I get the expected result:

Would you like to eat more cake?

^

Great, we got there, with this sequence:

diwimore

However, we can use ciw, to change the inner word. Change is "delete and replace", which gets you into insert mode. Now we have:

ciwmore

This is a subtle example of avoiding repeating and making commands compact.

cut, copy & paste

One of the most common uses of registers in vim, and really all you need here is to remember the commands. You saw d used above, for delete. This actually

deletes text and puts it in the default register ("). So if you want to paste it later, you can. To copy, use y for yank. All the rest

of the patterns above apply.

5ddjp, delete 5 lines, move down one line, and paste5dd5kp, the same, but move up5lines and paste there.d5WGP, delete 5 words (with any non-space characters), move to the end of the fileGandPaste them before the cursor.

There is one caveat here is that p will paste it after and P will paste it before the cursor.

Next Steps

So far, the above has gotten me to where I am able to navigate around single files and get comfortable editing large texts (like this blog post).

As I learn more, I'll update this series of posts with additional notes on my vim journey.

References

- Practical Vim by Drew Neil (google books link); this entire book is golden, but the first chapter The Vim Way really helped me understand what vim was trying to do.

- Vim Text Objects: The Definitive Guide

Ex stands for "ex mode", which comes from the ex editor

with apologies to House of Pain